In 2015, the MET Gala announced the annual theme for its highly anticipated event: “China: Through the Looking Glass”. Displayed on the header of the MET’s “select images page”, where commoners like me could take a digital gander at its fashionable offerings, was what I believed to be a vase.

Later, I discovered this image was actually depicting a Roberto Cavalli evening gown from his Fall/Winter 2005 to 2006 collection. This moment of misidentification, seemingly trivial, would become my gateway to this piece—what appeared to be a simple misunderstanding would ultimately serve as a lens through which I could examine broader imperial, gendered, and racialized frameworks.

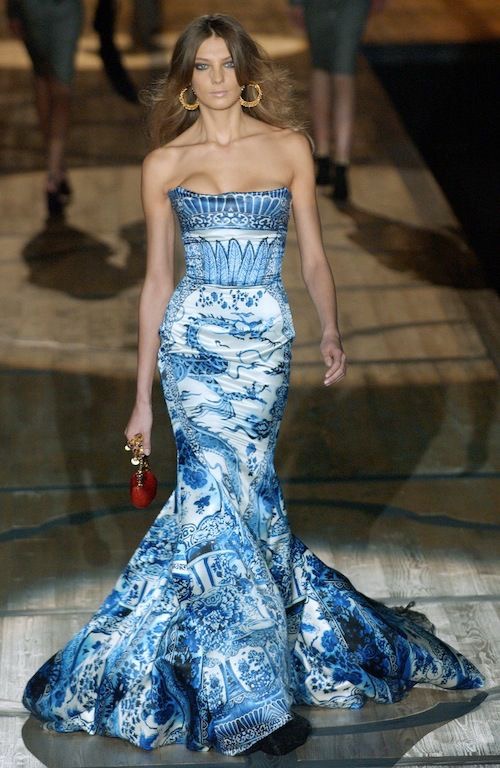

The dress itself is visually exquisite. Texturally, Cavalli was able to capture the layered, watercolor staining of chinese porcelain ink wash while preserving its intricate, brush-stroke like detailing. Morphologically, the dress is an hourglass, resembling both a vase and the ideal feminine figure, its contours and curvatures elegant and sensual. Most crucially, however, is how the dress is captured—from a low, angled perspective that draws the viewer’s gaze directly to the feminine form of the dress/wearer’s lower body, specifically her hips and backside (Figure 1).

Both the framing of the dress, which obscures its full length, as well as its visual detailing and silhouette, create a sense of disembodiment that blurs the line between object and personhood. The image is simultaneously feminine and sensual, yet also evocative of emptiness— the dress resembling both a vase and a woman. This blurred line raises questions about the material, the physical, and the ornamental. How does the framing of the dress, with its emphasis on the lower body, evoke colonial and gendered narratives about East Asian femininity, enduring through objectification and objecthood? How can we interpret the fusion of traditional Chinese motifs with the commodified representation of the female body in this design, and what does it reveal about the dynamics of cultural appropriation, objectification, and the racialization of East Asian women within Western, imperial discourse?

By isolating and highlighting the hourglass figure of the dress’s form, the photograph transforms the racialized body into an aesthetic object for consumption—visually and erotically. This process of transformation is linked to the ways in which East Asian women’s bodies are imbued with an aesthetic excess—an “ornamentalism” that is both racialized and gendered (Cheng, 2018). The Cavalli gown, in its sculptural contours, lies at the intersection of materiality and personhood, where its visual appeal is not just in the dress itself but in the way it evokes a particular vision of the East Asian woman, rooted in the imagination of East Asian femininity. By isolating the dress and obscuring the wearer (or even the possibility of a wearer), the photograph captures the disembodiment that Cheng describes—one where the body is not merely absent but displaced, replaced by the gown itself as a site of racial and sexual excess.

In the original image, the dress, imbued with Asiatic femininity through its porcelain-like texture and form, becomes a site where colonialist, Oriental imaginations of the “exotic” are projected onto the body (Said, 1978). The disembodied nature of the photograph allows the gown to stand in for an idealized, yet fragmented, notion of Chinese femininity—both culturally specific and racially coded, yet rendered “empty” and available for consumption. The notion of objectness in relation to the body thus becomes salient: the dress as an object, as an aesthetic construct, not only highlights the race and gendered qualities of its wearer but also gestures toward the disappearance of the wearer’s agency within the image. This dematerialized nonbody (Cheng, 2018) collapses into the ornamental, where the racialized body is rendered as a “thing” that exists to fulfill Western desires for exoticism.

As Cheng also notes, the seductiveness of inanimate objects, like the Cavalli gown, entices the viewer into a kind of “destabilizing eroticism”, where the lines between subject and object blur and the body becomes an aestheticized surface. The gown, in all of its regality and artistry, invites the viewer to lose themselves in a sensual experience of excess materiality, creating a space in which the object and its wearer become entangled. This entanglement not only defies binary critiques of objectification but also exposes the limitations of traditional postcolonial analysis—such as Said’s Orientalism and Foucauldian critiques—by demonstrating how racialized femininity is not merely a projection of colonial power but an aesthetic entrapment that seduces both the viewer and the wearer into a dynamic of corporeal and material abstraction.

What if, however, beyond a means of displacement, the dress itself becomes the vehicle for which class distinctions are articulated? The Cavalli gown, extravagant and lavish in its design, creates a visual display of opulence and artistry. Its position under bright museum lights, encased behind glass at the MET Gala creates the spectacularity, unreachability necessary for the exclusivity of the event in all of its glory—thus, the dress becomes symbolic and ornamental of Western elevated class and status (Cannadine, 2001) as well as a literal and figurative embodiment of imperial and capitalist values. Much like the teacup in Get Out—which becomes a performative object used to signify the entrenchment of racial hierarchies (Yang, 2021)—the gown operates as an accessory to the racialized spectacles of colonial power. In the same way the teacup signals the entanglement of race and class in the formation of white supremacy, the Cavalli gown reflects how “Chinese-ness”, through its performance of East Asian corporeality, is employed as a litmus for sophisticated extravagance.

As a space of elite cultural performance, the MET gala itself becomes a stage where “culture” is transformed into a high-art performance of global capital. Here, “Chinese-ness” is not simply displayed but metabolized—converted from a cultural signifier into a form of capital that can be consumed, traded, and strategically deployed. The dress itself becomes a complex technology of social differentiation, where the aestheticization of “otherness” serves as a mechanism of class distinction. By rendering “Chinese-ness” as an aesthetic of refined excess, the event produces a paradoxical space where cultural appropriation is simultaneously acknowledged and disavowed—an arena where Western elites can engage in a form of cultural ventriloquism that reaffirms their own cosmopolitan sophistication while maintaining a calibrated distance from the cultures they appropriate.

Yet, within this apparatus of colonial spectacle and cultural commodification, a more complex narrative emerges—one that resists the totalizing logic of imperial representation. If the previous analysis reveals the MET Gala as a machine of cultural appropriation, it simultaneously opens up unexpected spaces of negotiation and resistance. As Cheng suggests, this objectification may contain within it the seeds of its own subversion—a potential for a performance that exceeds the limited frameworks of colonial representation. Could the very mechanisms of objectification and display that seek to render “Chinese-ness” as a consumable aesthetic also create unintended ruptures, moments of slippage where the dress itself becomes more than a passive object of Western desire?

Drawing from Hoang’s insights about sex workers’ embodied resistance, we can read the Cavalli gown as a technology of strategic embodiment—where marginalized subjects manipulate systems of power by working within and against the very mechanisms of their own commodification. Its archival resistance operates through a strategy of productive ambiguity, or through its own kind of tactical, textile embodiment: the ambiguity of the wearer (or lack thereof), the ambiguity of shape, and the ambiguity of objecthood. Its morphological slippage—its ability to simultaneously evoke a vase, a feminine form, and a cultural artifact—creates what feminist theorists might call a “third space” of cultural negotiation. In this liminal zone, the dress performs what Homi Bhabha could describe as a form of “strategic misrecognition”—a mode of engagement that refuses the binary logic of colonial representation.

Crucially, this resistance is not located in any singular moment, but in the dress’s capacity to continuously destabilize the very systems of representation that seek to contain it. It operates as what Cheng might term as an “untranslatable” object—simultaneously “atavistic, Oriental, beautiful, and modern,” (Cheng, 2018 p.103) refusing any singular mode of interpretation. The dress becomes an embodied archive of cultural negotiation, a technology that exceeds the limited frameworks of colonial representation. By operating through aesthetic excess, the Cavalli gown works through existing systems of power by creating spaces of opacity, refusal, and misrecognition.

In this final rendering, the Cavalli gown becomes more than an object of cultural appropriation. It is a performative mechanism that reveals how racial and cultural identity can be simultaneously displaced and strategically deployed—an apparatus through which “cultural difference” is negotiated, consumed, and hierarchized. The dress stands as a testament to the ongoing processes of cultural translation, where displacement is not an end but a continuous negotiation of power, representation, and desire. The only question we can ask now is—who, or what, does the dress hold space for?

References

Bhabha, H.K. (1994). The Location of Culture (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Cannadine, D. (2001). Ornamentalism : how the British saw their empire. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

Cheng, A. A. Ornamentalism: A Feminist Theory for the Yellow Woman. Critical Inquiry 44, no. 3 (2018): 415-446.

China: Through the Looking Glass (n.d.) The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2015/china-through-the-looking-glass

Hoang, K. K. (2015). Dealing in Desire: Asian Ascendancy, Western Decline, and the Hidden Currencies of Global Sex Work (1st ed.). University of California Press.

Studeman, K. T. (2015, February 16) East Meets West: A First Look Inside the Met’s Spring Costume Institute Exhibition. Vogue. https://www.vogue.com/article/met-costume-institute-china-through-the-looking-glass

Said, E. W. (1978). Orientalism. New York, Pantheon Books.

Yang, C. (2021). Elephantine Chinoiserie and Asian Whiteness: Views on a Pair of Sèvres Vases. Journal of the Walters Art Museum (Vol. 75).